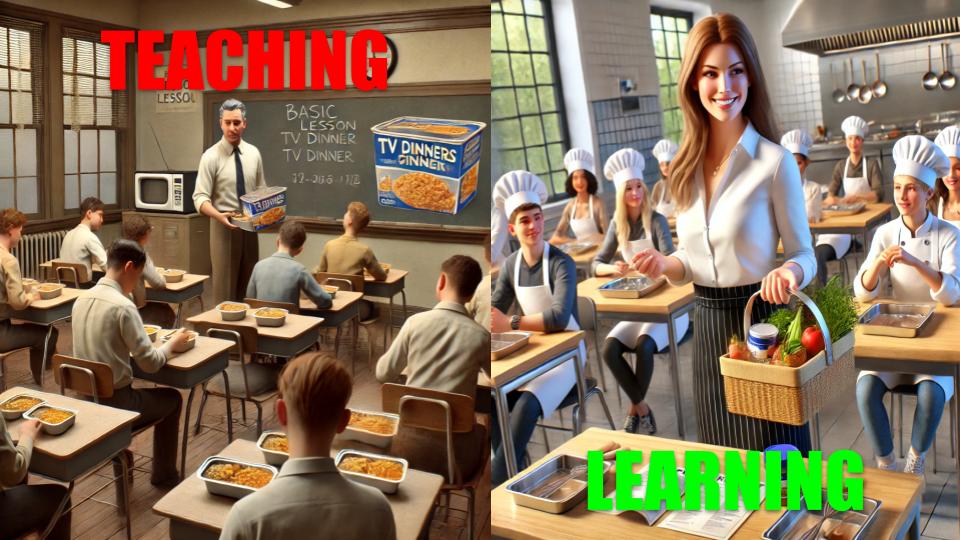

In education, teaching and learning are often used interchangeably, but they are fundamentally different. Imagine a classroom where the teacher hands out prepackaged TV dinners—complete, preplanned, and ready to consume. The students, functioning as mere cooks, only heat and eat what’s been prepared for them. Now, contrast that with a classroom where the teacher and learners collaboratively explore culinary skills and create dishes from scratch. The learners here are chefs, empowered to innovate, evaluate, and refine their creations. One is about consumption; the other, creation. One gets us the status quo; the other, gets us the improvement we’re always chasing.

Teachers as Chefs vs. Teachers as Distributors

The role of a teacher in a traditional “TV dinner” classroom is to distribute pre-made content. This approach is focused on efficiency, ensuring all students receive the same information at the same time. Teachers, like factory line supervisors, oversee a process designed for compliance and uniformity. Students, in turn, are positioned as passive recipients, expected to heat and serve the prepackaged knowledge without questioning its contents or source.

However, in a “culinary exploration” classroom, teachers step into the role of head chefs, guiding learners through the messy, iterative process of creation. They model techniques, provide foundational recipes, and encourage experimentation. Learners are no longer passive consumers; they become active participants, exploring ingredients, testing combinations, and refining their culinary creations. This shift in roles transforms the classroom into a dynamic kitchen where curiosity, collaboration, and creativity flourish.

Traditional teaching keeps the responsibility for success squarely on the teacher. If a student doesn’t “consume” the material, the blame often falls on the instructor. In contrast, a learning-focused approach distributes responsibility, challenging learners to take ownership of their educational journey. The teacher sets the stage, but learners must engage, question, and contribute to their own learning process.

Heating Prepackaged Meals vs. Designing New Recipes

Teaching often involves delivering preselected content through lectures, worksheets, and standardized assessments. This method, while straightforward, emphasizes memorization over mastery. Students focus on reproducing what they’ve been given, much like heating a frozen dinner: the process is predetermined, with little room for creativity or deviation.

In a learning-centered classroom, the process mirrors designing a recipe from scratch. Teachers introduce fundamental principles—basic cooking methods, the science behind flavor pairings—but learners must apply these principles to create something new. The process is iterative and exploratory. Learners might fail, adjust their approach, and try again, fostering resilience and critical thinking.

When learners create and experiment, they gain deeper insights into the subject matter. They learn not just the “what” but the “why” and “how.” This learning design aligns with Hattie’s concept of “Visible Learning,” where teacher clarity and ownership of learning result in significant academic growth (effect size 0.75). It’s the difference between knowing a recipe exists and understanding how to adapt it to different ingredients and tastes.

Consuming vs. Creating

The outcome of traditional teaching is often a uniform product: students who can replicate answers but struggle to innovate or apply knowledge in unfamiliar contexts. This approach might yield good test scores but does little to prepare students for the complex, adaptive challenges of the real world.

Conversely, learning-focused classrooms produce creators. Learners leave with the skills to tackle problems, collaborate with others, and think critically. They become adaptable chefs rather than assembly-line workers. By fostering creativity and problem-solving, this approach better aligns with the demands of today’s workforce, where employers value innovation over rote compliance.

Learners who are engaged in their learning are more likely to retain and apply their knowledge. The cognitive engagement required to create rather than consume encourages neural connections that make learning stick. Furthermore, the process of collaboration and self-directed inquiry prepares students for lifelong learning, an essential skill in an ever-changing world.

The shift from teaching to learning is not just a pedagogical adjustment; it’s a philosophical one. It requires us to move beyond the convenience of prepackaged education and embrace the messiness of exploration and creation. Teachers become guides, facilitators, and mentors, while learners take on the role of innovators and thinkers. The kitchen of learning may be noisier and less predictable than the orderly distribution of TV dinners, but it is also infinitely more rewarding. After all, education isn’t about serving up preheated meals—it’s about equipping learners with the skills to create their own recipes for success.